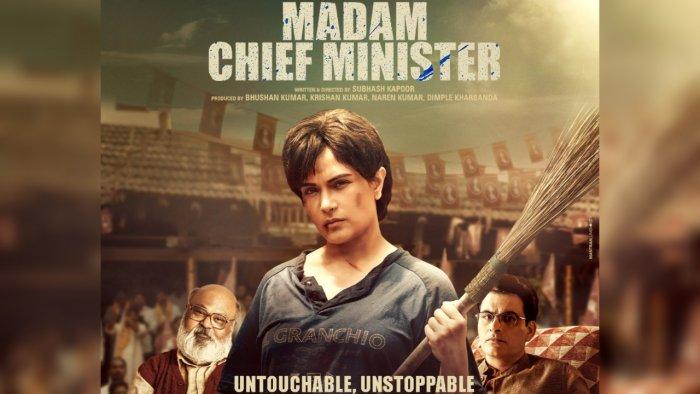

Subhash Kapoor’s new film, Madam Chief Minister (2021) has been in the limelight for all the wrong reasons. Although a work of fiction, the film is reported to be loosely based on the life of Mayawati, former Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh. The controversy caused by the film’s poster and tweets by Richa Chadha who plays the lead role are quite well-known by now. In short, the entire film project smacks of insidious casteism. The problem is obvious to those who recognise the unforgivable stereotyping propagated by the poster, which shows Richa Chadha in soiled rags, holding up a broom-weapon, with the tagline “Untouchable, Unstoppable”. However, there is a larger question here of ‘declarations of solidarity’ and the ethics of representation, that demand closer scrutiny. I will take the help of a 1970 documentary, Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris to try and elucidate this point further.

The American writer and activist, James Baldwin, migrated to Paris in November 1948, at the age of 24. It is here in Paris that he spent much of the rest of his life. In 1970, Terrance Dixon, a British filmmaker, approached Baldwin to make a documentary about ‘Baldwin’s Paris’. By this time, Baldwin had already established himself as a major writer, having published works like Giovanni’s Room (1956), Another Country (1962), The Fire Next Time (1965), and Tell me How Long the Train’s been Gone (1968). He had also emerged as an important voice within the American Civil Rights Movement -- which fought to end institutionalised racism and discrimination against Black Americans -- as well as within the gay right’s movement. This 27-minute film is a remarkable enactment of black resistance, allowing viewers to understand the complexities of ‘solidarity,’ which extends to our discussion of Madam Chief Minister.

The problem is obvious to those who recognise the unforgivable stereotyping propagated by the poster, which shows Richa Chadha in soiled rags, holding up a broom-weapon, with the tagline “Untouchable, Unstoppable”.

Terrance Dixon’s objective in making the film was to show Paris through the eyes of a black American writer, in exile in Paris. On the face of it, this sounds like a perfectly noble intention. However, sometime after shooting for the film began, Baldwin became less and less cooperative, and refused to talk about either Paris or his own literary work. Instead, he started enacting on screen the vexed relationship between a white European filmmaker and a black American in exile in Europe. Most of the film is shot in the Algerian quarters of Paris, a neighbourhood predominantly occupied by Algerian immigrants. Baldwin found friendship and support in these neighbourhoods -- the Algerians knew Paris, and helped Baldwin to get to know the city -- as he likened the Algerian experience in France to that of black people in America.

During the shooting of the film, Baldwin is accompanied by a young black man, possibly a student, who sometimes acts as an intermediary between the writer and the filmmaker. In one particular scene, the film’s crew are asked to shoot outside the Place de la Bastille, where the Bastille prison once stood, until it was stormed during the French Revolution in 1789. As the interview in this location begins, Baldwin’s young friend instructs the director to ask Baldwin why the Place de la Bastille is still among the most popular tourist destinations in Paris. Baldwin responds that it isn’t important whether it’s the most popular tourist destination or not; the response annoys the director, who accuses Baldwin of being reticent, not opening up, and obstructing the filmmaking process. “Why don’t you let us project you as you are, why don’t you let us tell the story from your point of view?’ asks Nixon.

The entire film project smacks of insidious casteism

Baldwin’s response to this question is profound: “I’m not so much a writer, as I am a citizen. I represent the political prisoner (a reference to the political prisoners previously held in the Bastille). I know something: what it means to be a black man in America or in Europe. We can be killed because of the colour of our skins. I am a survivor and a witness, and that’s all that matters. When a white man tears down a prison, he liberates himself. When I tear down a prison, I become a savage. Because you (to Nixon) are my prison. I’ve endured your salvation for too long, I cannot afford it anymore.”

This is a climactic moment in the film, marking a turning point. It is as if it was important for Baldwin to deny access to himself, until a point of break-down, where the relationship between the white filmmaker and his black subject was articulated. That this articulation takes place in a historic location, a symbol of liberation, is necessary to underline the continuing imprisonment of black people, coloured immigrants, and other marginalised communities.

To extend solidarity, is not an act of self-appeasing charity, available as ‘woke’ lip-service to one and all. An act of solidarity is a right that needs to be earned.

This encounter between the white film maker and the black American writer helps us understand the grave problems with the representation of a dalit woman, possibly the former Chief Minister of the State, in a role played by an upper caste woman, and directed by an upper caste man. Presenting the film and its message in an image captured in the main publicity poster - that of a broom-wielding, rag-clad, ‘untouchable’.

In a different but related matter, Professor Cornel West, political activist and philosopher, was recently denied tenureship by Harvard University. A lot has been written about this shocking episode, which has been condemned by progressive academics worldwide. One of the important commentaires offered has been by Suraj Yengde, post-doctoral fellow at Harvard and author of Caste Matters, who has worked closely with Prof. Cornel West in building a dalit-black solidarity network. Solidarity is an important political act; it is a call to action for social justice and dignity for all marginalised and oppressed people. Yet the question remains: is solidarity equal, is it neutral? To extend solidarity, is not an act of self-appeasing charity, available as ‘woke’ lip-service to one and all. An act of solidarity is a right that needs to be earned.

(Rashmi Sawhney is a cultural theorist and associate professor of Film & Cultural Studies, Christ University, Bengaluru)